Author’s note: This week, I’m taking a short break from the solar bike stories to share a bit about intergenerational friendships, which I’ve been mulling over for a while. I hope you enjoy this break from bike content, which will be back shortly! @Steve, I promise that technical details of the ride are coming shortly!

I recently did something kind of embarrassing.

I made a spreadsheet listing out my friends.

While I didn’t go as far as this woman, who engages in the (psychotic?) exercise of ranking her social network via a points system, I did put on the old business-student hat and build out a dozen columns to track some basic info: where I met folks, addresses for sending postcards, last time we talked on the phone, etc etc.

This exercise, undertaken half out of curiosity and half out of necessity in a network of pals who seem to change cities every year, immediately paid out some practical rewards A quick crunch of the data showed me that I hadn’t spoken to either Claire or Eric, two dear friends from my college / grad school days, in more than two years.

That’s pretty unacceptable, considering that both are people I used to speak to every day of my life during a season — creeping down to Eric’s dorm room to share the day’s gossip (9 years ago) and guffawing with Claire through group projects (5 years ago).

I’m happy to report that in both cases, we got on the phone last week and are making plans to meet up this fall. But this piece isn’t about mutual negligence; the spreadsheet also told me something else pretty interesting that sparked the flame of this essay:

I have a surprising number of friends who are older than me.

I’m not talking about the six-year age gap with my colleagues-turned-friends from time in consulting, or the law students I met in debate club. I’m talking about Gen-X friends who share birthdays with my parents. Even Boomer friends who are well into retirement.

Many of these are a product of proximity; most of them come from the two years I spent living in Berkeley, California, where a house full of twentysomethings was a total oddity on a quiet hilltop street far from campus.1 But like most relationships that last beyond a move past place, they’re glued together by a balanced blend of intentionality, good communication, and shared experiences. I’m lucky to count some of these cross-generational friendships among my most impactful; they’re people I text and call with frequency that sometimes exceeds how often I contact my actual grandparents.

Why make older friends? Anecdotes, data and musings to make the case.

I. To (mostly receive2) obligation-free advice

I’m lucky enough to be super close to my parents, and I would be 3000% lost without them.3 In general, I seek out their advice when I’m grappling with life’s questions, and their input is gratefully received.

But there’s something fundamentally freeing about not being bound to a person by the (grand)parent-child relationship. My older friends can cheer me on as I sail across the ocean or bike across the country with a little less patently obvious worry for my physical well-being. They can help me think through what cities to live in and what jobs to have without quite as much ‘skin in the game’ — they tend to be more relentless in their excitement for the unknown, an organic sounding board for who I’ve grown into in this moment of young adulthood, unburdened by who I was as a toddler or teen.4

And when they give pointed advice — well, let’s just say I tend to listen a bit more closely.

II. To learn how shared moral values play out across lifetimes

My older friends hold a range of careers; they have many children or none at all; have moved a dozen times or lived in the same house for 30 years. But (see point I), given these relationships aren’t obligation-based, we usually share some framework of moral values. Maybe we’re all environmentalists. Maybe we’re avid readers. Maybe we all just really, really like riding bikes.

Whatever it is, my older friends tend to embody things I’m trying to nurture within myself. And from knowing them, I get a glimpse into the future of what life looks like when you live in line with those values. I tend to like what I see — whether it’s the elegant maintenance of decades of sporting or rediscovering the joy of playing a musical instrument in your 60s.

And on the flip side, my older friends then get to see how similar beliefs play out in the lifestyle choices of a different generation. I’ve had a ton of conversations about my decision to take time away from conventional work; most of my older friends have been supportive and curious, if not flat-out a bit envious of the winding path that millenials often take before settling in a particular place.

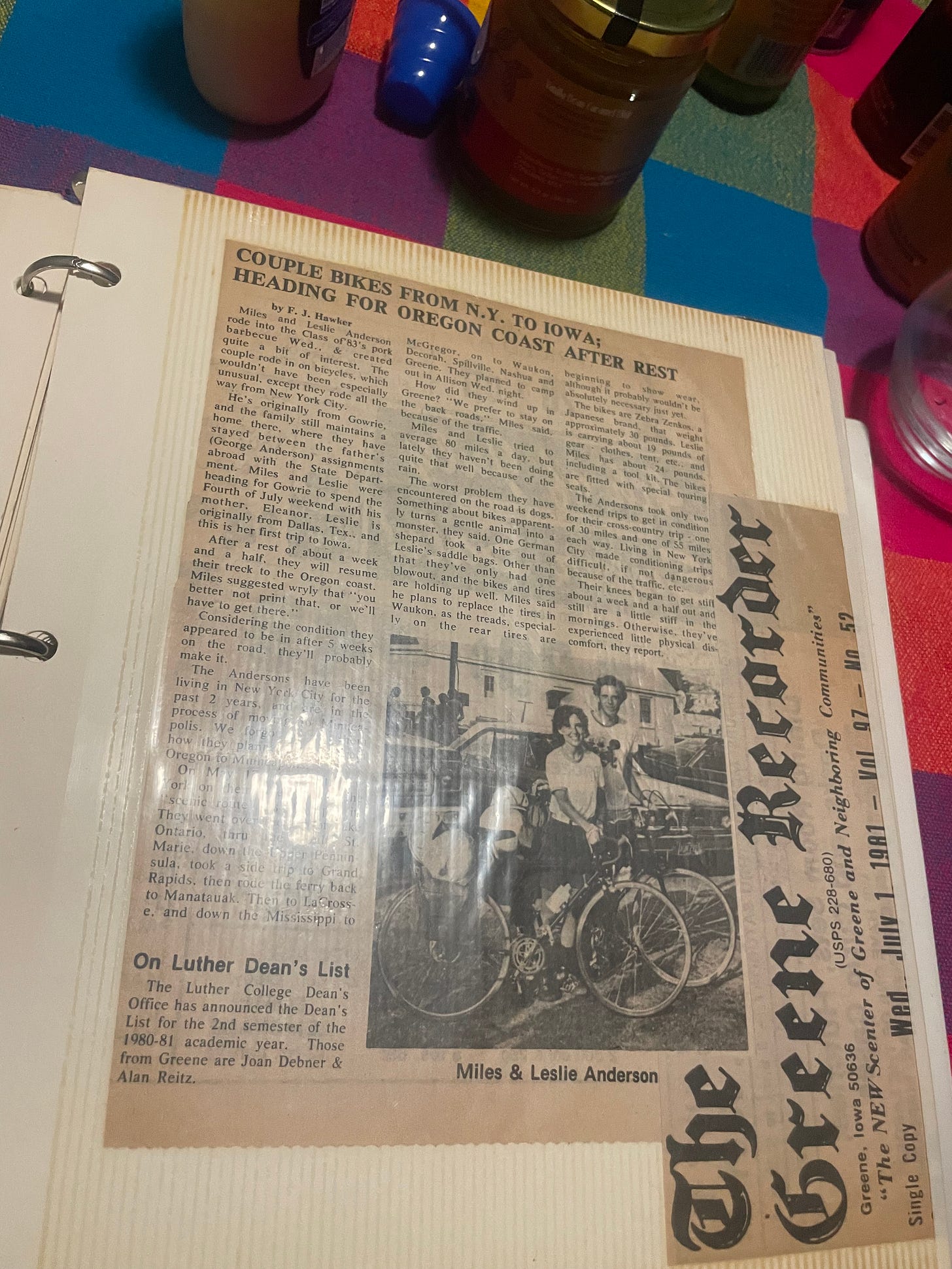

Anecdote: I just stayed with Miles and Leslie in Minneapolis for three days. They’re an incredible couple of retirees who have lived a wealth of experiences: biking across the USA in 1981, living and working in Belgium, and are now loading up to bike across France for the second time in September. I can’t think of the last time I met two people who I was so keen to emulate.

III. It’s good for everyone’s health

One in three Americans feel lonely every week.

Gen Z is by far, the loneliest generation.

Studies show that, the more diverse your social life is, the better it is for your health and well-being. Cultivating friendships among different age groups removes certain toxic peer-group insecurities — like competition and comparison — while allowing for the benefits uninhibited joy and mentorship.

The NYT says it better than I can, but these relationships cut both ways.

Connection that is life-affiriming and energizing? I think we could all use a little more of that, no matter who we are or where we come from.

IV. There are some classiness perks

On Vistamont, I lived across the street from Marie-Paul and Richard, a couple with an impressive library that could only belong to the professorial set. Our house full of hungry triathletes trekked over for a *casual* dinner one evening, only to be greeted with:

+ a full spread of appetizers (+ white wine)

+ a fragrant tajine (+ red wine)

+ and gluten-free crepes.5

We stumbled home, on a Tuesday, fully sated and a bit sotted. Given the fact that most of my household was subsisting on a lot of Costco peanut butter and oatmeal at the time, the whole thing was an extremely indulgent moment for us. A case study in warm generosity without any anticipation of reciprocity that moved the heart.6

Also, Richard played several caprices on his violin for us. And he was far better than most of the people I was in high-school orchestra with.

V. Flexing different communication models

I recently picked up a phone call from an unknown New Jersey number. It was Peter, a railroad retiree I met on the Loneliest Road in America. I was initially confused — why was this barely-acquaintance calling me? It turned out — he was just checking up on my progress and well-being, and that he didn’t know how to text — so a phone call was the natural way to do so. We talked for less than five minutes before he wished me luck and promised to call again.

This short interaction from a new acquaintance was, admittedly, a lot more moving than the occasional spurts of texts I exchange with friends I’ve known for years about the bike trip, at times. There’s something special about hearing someone’s voice, or reading their handwriting, that vaults above reading a short text or watching their digital call-outs via Instagram stories.

My older friends tend to be more intentional with how they reach out — asking me, in turn, to be better about responding to messages or to make the gesture of a handwritten postcard. I was recently super touched when David and Sandrine sat for three hours in traffic to bid me and Polo goodbye as we set off on our cross-country bike trip.7

Through these relationships, I’ve made strides in going deeper in messages, or taking the time to write out a real letter instead of offering a perfunctory *whats up*. These lessons, learned from cross-generational communication, are seriously upleveling when I take them to my text-heavy friends. But that being said…

I do owe many of my intergenerational friendships to the power of the Internet. Using tools like Couchsurfing and Warmshowers, I’ve been lucky enough to form friendships with different-generation friends across the world; from Kasia and Robert in Berlin, to Eleanor and Martin in Davis, California. Digital communication might contribute to the ‘loneliness epidemic’ — but in some ways, it allows us to connect with people we might not otherwise encounter, or keeps us connected to those we might otherwise lose touch with (@Caitlin D. - your shoutout is coming next week).

But it wouldn’t be on-brand for this Substack if I didn’t somehow relate these musings on intergenerational friendship back to climate action. As I’ve traveled and met with a bunch of climate people over the last year, I’ve decided on three things:

(1) young people have a lot to say on climate action and look good on camera, which is why we get a lot of media attention —

(2) older people have been doing this for a lot longer than we have, with far less thanks because they had to deal with the OG climate deniers and —

(3) know how to actually get things done because they’ve spent decades in the fight.

My all-time favorite climate activist is Bill McKibben, a mild-mannered, boomer-age Vermonter who recently blew my mind with this sharp assessment of Tim Walz, the VP nominee for the Democratic party.

For most of America, having neighbors has been more or less optional for the last 75 years. At the moment, if you have a credit card, you can get all that you need to survive delivered to your front door. But the next 75 years are going to be harder: as the climate crisis breaks over us, we’re going to have to relearn the skills, and the joys, of neighborliness. It is entirely clear, from the testimony of his former students and of everyone else in his town, that Walz has those skills. He is a good neighbor.

Those skills help not just in time of crisis. They also, potentially, help as we work to build out the renewable energy we desperately need. In too many places a NIMBY approach has taken hold, when what we need is a Yes In Our Neighborhood willingness to build the local energy economies we require.

My experience of being a good neighbor has been, in large part, shaped by being a good neighbor to folks from different age groups than me. As a late-twenty-something, I’m truly excited about the next stage of neighborliness from my end — helping with lawn chores and baking banana bread, rather than inviting my neighbors to our backyard ragers. But no matter what you bring to the table — remember that you’re offering something that someone else needs. Neighborliness is a happiness; intergenerational neighborliness is a lasting joy. So here’s to more door knocks and fewer credit card transactions.

Maybe I’ll revisit this essay in 30 years. I’ll be 57 then, with grey hair of my own.8 I hope to be a kickass Warmshowers host, but like my new friend Miles from Minneapolis, still crushing massive bike tours of my own.9

If you’re one of my older friends reading this essay, please chime in: what do you get out of your intergenerational relationships? I’d love to think on it further.

Much love, Megan

Just ask my old neighbors or roommates what the general reaction was to our future-themed party, Fall 2021.

I don’t have much advice to give to my older friends, because good advice comes from wisdom, and I’m far too green to be wise.

Evidence: my Dad and I have matching tattoos.

Dramatic in both cases, I believe.

I have not truly forgiven Jonathan for the long period of being gluten-free where he would eat around the crust of various baked goods I made for the house.

Although we did proceed to invite Richard and Marie-Paul to many Vistamont ragers, and they raged.

Yes, the distance from South Bay to East Bay can be that long.

Although hopefully not much, if I am so lucky as to have my mom’s genetics.

But not in Wisconsin. I think the Great Lakes region is super cold.